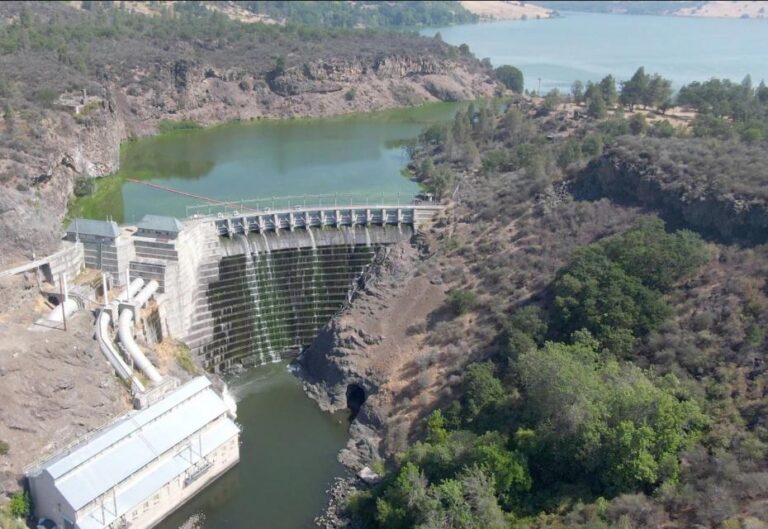

The Copco No. 1 dam on the Klamath River is slated for demolition in 2024. Photo by Stormy Staats/Klamath Salmon Media Collaborative

The Klamath River Basin was once one of the world’s most ecologically magnificent regions, a watershed teeming with salmon, migratory birds and wildlife that thrived alongside Native American communities. The river flowed rapidly from its headwaters in southern Oregon’s high deserts into Upper Klamath Lake, collected snowmelt along a narrow gorge through the Cascades, then raced downhill to the California coast in a misty, redwood-lined finish.

For the past century, though, the Klamath – a name derived from a Native American term for swiftness – hasn’t been free-flowing or flush with salmon. Dams block fish from the upper watershed’s spawning grounds. Reservoirs host toxic algae blooms. Parasites and pathogens that can flourish when dam-regulated flows are low have wiped out salmon by the tens of thousands.

“A dam removal of this size is unprecedented. Everyone, I would say, is watching this.”

—Sarah Null, watershed sciences professor at Utah State University

The Klamath’s ecological vitality — above and below the dams — has diminished along with longstanding tribal connections to the river.

Now, after decades of tireless negotiating among myriad parties, the Klamath is being given a chance to return to a more natural state. Construction crews this summer are taking out the first of four essentially defunct hydroelectric dams choking a 64-mile stretch, with the remaining three slated to come out by the end of 2024 in the largest dam removal project ever undertaken.

But several questions remain: Will the Klamath’s damaged ecosystem recover? How will salmon respond, and can they […]

Full article: www.watereducation.org